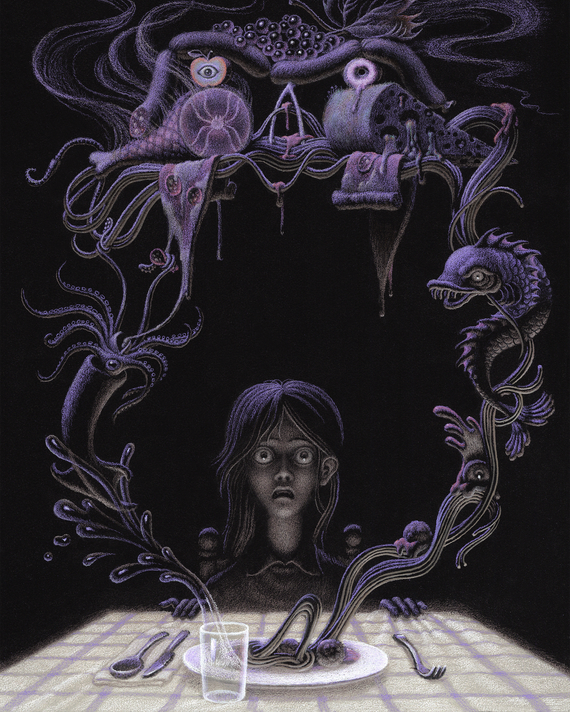

Illustration: Daniele Castellano

Laura still wonders how different things would be if she and her husband, Mark, had simply chosen another camp. It was June 2021, and after months of virtual kindergarten, they sent their then-almost-6-year-old daughter to a summer program at a local school. The camp would be a brief reprieve before Amelia, an only child, started first grade, and Laura was sure she would love it. She was outgoing, the kind of kid who didn’t hesitate to approach someone new on the playground and start a game.

So Laura was surprised when, after the first day, Amelia told her she didn’t want to go back. At pickup a few days later, she pleaded again not to return. She said the woman who ran the camp often yelled and, at lunchtime, wouldn’t let Amelia leave the table until she finished all her food. Laura spoke to the woman — Amelia didn’t need to eat every morsel, she told her — and assumed the problem was resolved.

Camp ended, but over the next 12 months, Amelia would sometimes stuff her mouth with food, panic that it was too much to swallow, and spit it out. Laura told Amelia she needed to chew her food properly or she could choke. Amelia asked what would happen next. Two close family members had fallen severely ill with COVID, and one of them had died. Amelia became fixated on death. She wanted to know: What happens when you choke? You can’t breathe? Well, what happens if you can’t breathe? Then you die?

Amelia hadn’t been an anxious child, but she became increasingly sensitive to the world around her. She tensed up when people talked sternly; once, when a substitute instructor shouted in gymnastics class, Amelia rushed over to Laura and, through tears, begged to leave immediately. Her clothes started to bother her. At first, she didn’t want to wear dresses. Then she would wear only certain pants and a select few shirts. By the start of 2023, she was down to one outfit that Laura and Mark washed daily: a pair of fuzzy blue Cat & Jack pajamas with stars and planets and the cotton underwear she insisted felt more comfortable than all the others. When she tried to put on school clothes, “she’d work herself into a panic attack,” said Mark. “She’d say, ‘It’s too itchy. It’s too scratchy. It’s too tight. I can’t wear it. It hurts.’” At night, Amelia resisted falling asleep, convinced that if she closed her eyes, she might not wake up. Mark and Laura took turns in her room until she drifted off, which left everyone drained.

Her parents had her evaluated for autism, but doctors determined that while Amelia was hypersensitive, her behavior was rooted in anxiety. This made sense to Mark and Laura: Studies suggest that generalized anxiety disorder may run in families, and Laura had been diagnosed years earlier. As a child, she had an outsize fear of death; in adulthood, she tended to operate as though “everything is a fire drill,” she told me. If it took Amelia too long to get her shoes on or eat breakfast, Laura would grow frantic, worried that her daughter would be late for school and get in trouble.

One day in January 2023, Amelia overheard Mark and Laura discussing the sign-up deadlines for different summer camps and began to fret. That evening, while eating a chicken nugget, she yelled out to Laura that she was choking. She had recently watched an episode of The Baby-Sitters Club in which a character chokes on her dinner. That part of the scene lasts only ten seconds, but the camera focuses on the girl’s terrified face while she struggles to breathe. Amelia wasn’t actually choking — she could speak — but her whole body had clenched and made her feel as though she couldn’t swallow.

Previously, Amelia ate a wide-ranging diet, but after the chicken-nugget incident, she began to refuse solid foods. Within a week, she would consume only yogurt and liquids. “We would buy every drink that she could possibly want — chocolate milk, juice. We were desperate,” said Laura. “And it got worse every single day.” Amelia cut out the yogurt, convinced she would choke on it. A couple of weeks later, she rejected liquids, too. She began spitting into a napkin, unable to swallow her own saliva. It felt like something was stuck in her throat, Amelia said. She believed if she did try to swallow, she would choke, suffocate, and die.

Dinner turned into a nightly standoff: Amelia on one side of the table, growing thinner and frailer, Mark and Laura on the other, their panic mounting. Sometimes, they tried coaxing her. Other times, they couldn’t help but yell. “We didn’t know how to deal with it. Like, ‘Why can’t you eat?’” said Laura. It felt like a failure. They tried to quiet their terror by leaning on what one may believe to be a biological fact — that humans are wired for survival and, eventually, a child will get hungry and want food. “I kept thinking, Mother Nature’s going to kick in here,” said Mark, who asked that his family’s names be changed owing to the detailed account of his daughter’s medical history being shared. (Some other names have also been changed.) Instead, Amelia’s hunger response seemed to have shut off. If they tried to feed her, she would spit out the food.

Doctors looked for a physical explanation for Amelia’s sudden inability to swallow. At urgent care, providers said they didn’t see any obstruction and told Mark and Laura to contact Amelia’s pediatrician, though when they called to set up an appointment, the pediatrician had no immediate availability. An ear-nose-and-throat specialist suggested Amelia might have eosinophilic esophagitis, a chronic inflammatory condition that can be triggered by allergies or acid reflux. That doctor sent them home with nasal spray and antacids and suggested they see an allergist.

By the end of that February, roughly a month after she had stopped eating normally, Amelia weighed 37 pounds. Mark and Laura called doctor after doctor, including multiple psychologists, but those listed under their insurance no longer accepted their plan, didn’t treat patients that young, or couldn’t see them for six months. Amelia, increasingly malnourished, began screaming, cursing, and throwing things. “She was just turning into an animal,” said Mark. “We did not recognize our own daughter.”

The morning of February 22, Mark and Laura took Amelia to the emergency room. Doctors were alarmed — a blood test showed Amelia was in danger of heart failure. They transferred her to a hospital with a pediatric department, where a gastroenterologist inserted a feeding tube up her nose and into her stomach, allowing her to consume a nutrient-rich formula without swallowing. An endoscopy again confirmed the absence of a physical obstruction or abnormality. Finally, a doctor sat down with Mark and Laura and gave them a name for what their daughter was experiencing. They suspected that Amelia had ARFID, or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, a psychiatric diagnosis, often emerging in childhood, that can range from eating a very limited number of foods to refusing food altogether. Like many other parents, Mark and Laura hadn’t heard of ARFID. It seemed the numerous doctors who had seen Amelia over the past month hadn’t either.

ARFID is a fairly new addition to the modern parenting lexicon: A behavior far more severe than pickiness, it’s an eating disorder provoked not by the desire to change one’s body but by the fear of food itself. Only in the past few years has the acronym begun circulating on playgrounds and in school nurses’ offices, and it’s not uncommon for parents to first stumble upon it on their own — on Reddit threads, in Facebook groups, on Instagram or TikTok. (This month, Real Housewives of Orange County star Emily Simpson shared that her 10-year-old son has the disorder.) One mother told me she’d learned about ARFID after searching online, “Why is my 5-year-old eating absolutely nothing?” “Bulimia came up. He doesn’t have bulimia,” she said. “Then I saw anorexia, and I was like, He doesn’t have anorexia. And then I scrolled more and it said, ‘Does your child have ARFID?’ And he had every symptom.”

Doctors who specialize in eating disorders say they have seen an increase in diagnoses over the past several years, and a recent study found that, among children, the number of inpatient hospital discharges in which ARFID was the chief diagnosis doubled from 2017 to 2022. “There was this explosion almost six years ago, when we had a bunch of cases coming into the hospital,” said Heather Kertesz-Briest, a clinical psychologist who used to work at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Equip, a telehealth company specializing in eating disorders, treated more than 1,000 ARFID patients in 2024 — a 144 percent bump from the previous year. And Beat, a U.K.-based charity that runs eating-disorder hotlines, reports that there were nearly seven times as many calls about ARFID in 2023 than in 2018. There is limited data available, but one review estimates that up to 5 percent of the population has it, and a 2023 screen of 50,000 adults suggests it may be as common as anorexia.

While classified as an eating disorder, ARFID may be more easily understood in many children as an anxiety disorder that centers on food. Its rise coincides with a pediatric diagnostic boom in mental-health conditions as more and more children are treated for generalized anxiety disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and ADHD — raising the question of whether they are a generation maladapted to the world around them or the first generation to be thoroughly understood. ARFID often orbits these diagnoses, a disorder that can become the most physical manifestation of what’s happening in a child’s mind. “That primal instinct to feed your kid, that is millions of years of evolution,” Mark said. “It’s scary for your kid to not eat and not drink and to not understand, What’s going on here? ”

ARFID existed long before doctors gave it a name. For decades, health professionals working in hospitals and eating-disorder clinics encountered patients who were severely underweight from not eating but who didn’t qualify for an anorexia diagnosis because they weren’t trying to lose weight or grappling with body dysmorphia — instead, they were disinterested in food, felt disgusted by it, or feared it. Twenty years ago, “the way we thought about some cases was that maybe the patient has anorexia secretly but they have a lack of insight into it,” said Jennifer Thomas, a psychologist and co-director of the Eating Disorders Clinical and Research Program at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Until 2013, the year ARFID entered the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the closest label was “feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood,” a code for children under 6. But the age cap made the label inapplicable to many patients, and it wasn’t widely used or researched. Unable to find meaningful literature on the condition, authors of the DSM-5 spoke with psychologists and doctors who worked with eating-disorder patients and identified a specific patient profile: a person with sufficient access to food who wasn’t concerned with altering their body shape, and who restricted or avoided eating to a point where they lost significant weight, didn’t get enough nutrients, and/or experienced mental and social distress. These patients were, on average, younger and more likely to be male than those with anorexia. They lived not just in North America and Europe but also in Oceania, Southeast Asia, and Japan. When Thomas and her colleague eventually published a treatment manual for ARFID, they quickly got requests for editions in other languages, including Turkish, Italian, and Spanish.

The DSM-5 authors identified three presentations of ARFID, which themselves can feel like different diagnoses, though some patients fall into more than one category. One subgroup is made up of those who are simply uninterested in food, often from birth. Many were, as newborns, admitted into neonatal-intensive-care units, where they were put on feeding tubes. The tubes are lifesaving, but they bypass the tactile experience of eating, which can lead to an oral aversion. Some tube-fed babies struggle to develop hunger cues or learn the mechanics of swallowing. Years later, they may still lack the two major motivators to eat: They don’t feel hunger, and they don’t enjoy food.

A second category is made up of people who have a sensory aversion: They tolerate certain tastes, smells, temperatures, and textures and feel disgusted by most everything else. Many of these patients are neurodiverse, and while it’s common for people with autism to have sensory sensitivity to food, “where ARFID rears its head is when the sensory experience is so discordant, so displeasurable, that it creates a full-body anxiety response,” said Matt Zakreski, a clinical psychologist who specializes in neuropsychological developmental disorders. “It’s analogous to the difference between having seasonal allergies and having anaphylactic shock.”

The most sudden ARFID cases fall into a third group: children like Amelia who develop a fear around eating, often after experiencing a traumatic event. Kellee Lanza-Bolen, a mother in Virginia, said her 8-year-old daughter stopped eating after choking on gummy candy she got in her Christmas stocking. The next month, her daughter was admitted to the hospital, where she was eventually diagnosed with ARFID and put on a feeding tube. Lanza-Bolen was confused; she had seen videos of Hannah Lea, a 9-year-old girl who chronicles her life with ARFID on Instagram and TikTok. But Hannah has sensory-processing issues. “When I heard ARFID, I said, ‘Well, no, because my kid doesn’t have sensory issues,’” Lanza-Bolen said. Her understanding of the disorder shifted once she learned it can be a response to a harrowing experience, similar to a person who becomes terrified of driving after a car accident. She now compares her daughter’s anxiety around swallowing to “the same fear that keeps you from getting too close to the edge of a balcony or the top of a building.”

As the disorder gained recognition, diagnoses naturally increased. The way Zakreski sees it, the embrace of the label stems from clinicians developing a more holistic understanding of the brain. “For a long time, we treated mental health through the medical model: You have a broken ankle, that’s it. You have pneumonia, that’s it,” he said. “Now, we know that any change to the brain predicts a lot of other changes, that one neurodivergence predicts other neurodivergences at a significantly higher rate.” One study, for example, suggests more than half of ARFID patients have autism, a disorder with a strong hereditary link and rising diagnostic rates. In Kertesz-Briest’s practice, nearly every single child with ARFID she sees also has an anxiety disorder, the most common mental-health diagnosis in adolescents. Meanwhile, food allergies, which can make eating feel like a fearsome game of roulette, are increasingly common among children, and William Sharp, the director of the Multidisciplinary Feeding Program at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said it’s no coincidence that more than 30 percent of his patients with a food allergy likely also have ARFID. Premature birth is also a known risk factor for feeding problems that can develop into ARFID, and as of 2023, nearly 10 percent of newborns are admitted into a neonatal-intensive-care unit.

ARFID, in other words, is poised at the juncture between the physical and the psychological, the genetic and the environmental — both something that’s existed under parents’ noses all along as well as a consequence of our contemporary age. And at a time when parenting culture is more attentive and anxiety-ridden than ever, the mystery ARFID presents mirrors the larger questions at the top of every parent’s mind today: How much control do we have over our children, or how much control should we exert? When does our vigilance contribute to our children’s anxieties, and when is it the only thing keeping them alive?

After Amelia was put on a feeding tube and stabilized, she was transferred to another hospital, which had an eating-disorder clinic. The clinic was disorienting. Amelia was the only 7-year-old there, and in the waiting room, her family found themselves sitting between toddlers with feeding issues and tween and teen girls. Mark gazed at the other parents, all of whom looked “like a bomb had gone off,” he said.

For the next few weeks, he and Laura split their time between the clinic and their home, three hours away with traffic. Their marriage, bruised by the past few months, began to buckle. “We had a ton of angst about, How did we mess up our daughter? ” said Mark. “When your kid gets cancer, you can’t blame your spouse. When your kid has something more psychological, you start asking, Did I cause this? Was this something I did or said? Was it something my spouse did or said? ” Laura worried that Mark’s frustration with Amelia — he had gone from being the calm, steady parent to raising his voice — had unnerved her. Mark worried that it was Laura’s anxiety that had rubbed off. “Why did you tell her she’s going to die from choking?” he asked. Meanwhile, at the hospital, Amelia was in constant agitation. She tried to rip out her feeding tube. She screamed and spit, asking why the doctors weren’t helping her. Her mind was still making her body believe she couldn’t swallow.

ARFID, like the diagnoses it often accompanies, exists along a wide spectrum, with cases like Amelia’s at the most severe end. Many children with the disorder will eat but only from a very short list of foods. Those with a sensory aversion in particular tend to have rigid preferences, almost always gravitating toward carbohydrates. Jennifer Thomas, the psychologist who published the ARFID treatment manual, said this is true across cultures: In Boston, where she is based, the food of choice is Annie’s macaroni and cheese, while colleagues in Mexico see a preference for tortillas, and in Asia and the Middle East, rice. Processed and packaged foods — consistent in shape, size, and taste — are also deemed “safe” by children with ARFID, and doctors in the U.S. see a strong proclivity for McDonald’s chicken nuggets and frozen dinosaur-shaped nuggets. The difference between “safe” and “unsafe” can be minute — at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, kids getting treated for ARFID stopped eating the puréed chicken nuggets they had been consuming for weeks when the brand the hospital used tweaked its recipe.

In many ways, these cases can prove the most challenging to navigate. A child who won’t eat at all presents a clear crisis, while a child who eats a few specific foods and isn’t in imminent danger of starvation leaves more room to question what’s pathological and what’s not, what may just be a child asserting their independence and what warrants medical attention. Plenty of general practitioners still aren’t aware of ARFID, and one study found it can take almost three years to get a diagnosis after the onset of symptoms, more than double the average time for someone with anorexia.

Sarah, a mother in New York, was alarmed to learn from a teacher that her daughter, then in preschool, had been eating only apples for lunch and refusing everything else. The pediatrician assured her and her husband it would pass — in the doctor’s office, “the philosophy was ‘Well, she’ll eventually get hungry and eat the food that’s on the table,’” Sarah said. Maybe, they thought, their daughter was simply strong-willed. They agreed that accommodating her increasingly specific food requests would reinforce the behavior. Her diet moderately expanded. But when she was 8, she was being bullied at school, the family’s nanny left, and suddenly she wanted only applesauce for two weeks, saying anything else “hurts my body.” One night, when getting her daughter dressed for bed, Sarah was startled to see how thin she had gotten. At an eating-disorder clinic, Sarah’s daughter was diagnosed with ARFID. Later, after a full psychological evaluation, she was also diagnosed with ADHD and generalized anxiety disorder and flagged for possible autism. Now, Sarah stays alert to when her daughter wants more applesauce than usual, mindful that it could be a warning sign.

This is a generation of parents who have made food a terrain of their success as caregivers, who see mealtime as a ritual for connection and are highly conscious of what exactly their children consume. When Tania of Perth, Australia, got pregnant at 38, she decided motherhood “would be my next career.” She took courses on sleep training, read parenting books, learned how to blend her own purées. But after a traumatic birth that broke her son’s collarbone, followed by a series of respiratory infections and a tonsillectomy, her son, now 5, didn’t take to food, accepting only milk and bread. When she put blueberries on his plate, he would pretend to eat them before throwing them on the floor. Instead of bonding with her son at mealtimes as she had envisioned, Tania began to anticipate his resistance. Once, she said, “I put the food on the table and burst into tears.”

Tania and her son’s world grew smaller. Mommy-and-me classes were stressful; he tired out easily from not eating enough, and she felt embarrassed when other parents pulled out lunch boxes with fresh fruit while her child ate only puffed snacks. Finally, a dietitian recommended a book called Helping Your Child With Extreme Picky Eating, which described ARFID and included a chapter on parents blaming themselves for their child’s difficulty with food. Upon reading it, Tania said, “weights were lifted from my shoulders.”

When he was 4, Tania’s son drew this self-portrait with a dark scribble on his stomach at school. He was diagnosed with ARFID shortly after.

Parents of children with more moderate cases of ARFID — those kids who eat a few foods — describe living in fear of others’ perceptions. They worry that fellow parents think they’re lazy and don’t want to cook or that their whole family must subsist on Goldfish and chicken nuggets. (Some patients who eat a rigid diet of high-fat or high-carb foods may even be overweight. In a private ARFID Facebook group, a few parents post about their children being diagnosed with diabetes.) “Parents say to me, ‘Well, you just need to make sure they eat variety,’” said Sarah. While her daughter has ARFID, her other child eats almost anything. “I’m like, We have all the fresh fruits and vegetables. My kids were raised exactly the same. In terms of nature versus nurture, their nature is completely different.” One Christmas Eve after being pressured to eat, her daughter with ARFID began hyperventilating at the table in front of their extended family. A relative pulled Sarah aside and told her such a disturbance can never happen again. “They think it’s misbehavior, that we aren’t disciplining her,” she said.

Eventually, some parents told me, friends and family stopped coming over for dinner. “You could tell they didn’t want to be around it,” said Stacia Kareh, a parent in Nashville. As a newborn, her son had been put on a feeding tube; at 5, he suddenly stopped eating the short list of foods he had once tolerated. Mealtimes became “a fight to get every calorie into him. It was begging, pleading,” she said. Even after undergoing treatment, her son, now 7, still negotiates every bite. “He argues with us, like, ‘Well, if I eat this, how long will that give me to live?’”

To an outsider, these cases may look like choosiness or defiance, but “ ‘picky eating’ undermines how severe this is,” said Sharp, the director at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. “We’re seeing kids with autism who only eat two foods. These kids develop rickets; they develop scurvy.” In extremely rare instances, the malnutrition can become fatal. Lucy Morrison, a mother in the U.K., told me about her son, Alfie, who had nonspeaking autism and restricted his eating for his entire life, primarily consuming baby crackers and porridge. In 2021, Alfie fell off a small bench at school and began limping, then grew increasingly lethargic. A week later, he had stopped eating anything, but the pediatrician told her, “He’s acting like that because of his autism.” A few days later, Alfie, 7, went into cardiac arrest and died. Only two years later was it determined that the malnutrition brought about by ARFID had caused his heart to stop. Lucy said the first person to tell her the diagnosis was the coroner tasked with investigating his death.

This past winter, I met a woman named Grace and her son for breakfast in Manhattan. Grace ordered soup and a coffee, but her son, then 10, had already eaten his standard morning meal of glazed doughnuts from the Dunkin’ near their home; he says he can tell when a doughnut is made at other locations. The boy, who has been diagnosed with ARFID, ADHD, and generalized anxiety disorder, was polite and matter-of-fact. He described how he lives with an almost constant, vague stomach discomfort that makes it hard to tell when he’s hungry. It’s exacerbated by the appetite-suppressing effects of the Ritalin he takes for ADHD and the constipation from his diet of processed foods.

Until he was 3, Grace told me, her son ate everything from mashed vegetables to pea soup to sausages. But when he started day care, he refused to eat the provided lunches, holding out even as the teachers encouraged him with increasing desperation. Grace, who was working full time, started giving him packaged snacks on the drive home. Her son developed a strong affinity for them and began rejecting most other food — a behavior that worsened over time. Now, while the rest of the family has dinner, he eats his own meal of McDonald’s chicken nuggets and French fries with Sprite. At school, the smells in the lunchroom are sensory overload, so his safe foods are kept in the nurse’s office: gummy bears and sour gummy worms, Cheez-Its, Oreos, and Pirate’s Booty. He takes multivitamins to supplement nutrients. Grace has two degrees, one in psychology, and she knows how this sounds. Still, she said, what else can she do? Her son doesn’t have hunger cues, and without his preferred foods, he simply won’t eat.

ARFID’s emergence as a diagnosis coincided with a seismic shift in parenting culture. “We know so much more about the brain now than we did 30 to 40 years ago, and we’re raising our kids with a better understanding of how their brain develops, including their emotional-regulation skills and sensory processing,” said Kertesz-Briest, the clinical psychologist. Behaviors that past generations of parents might have viewed as “bad” and warranting punishment are today apprehended through a more compassionate lens. One woman I spoke with, who has a son with ARFID and generalized anxiety disorder, often thinks of the way her parents got her sister to eat when they were young. Her sister was picky, and their parents did “the same thing any parent in the ’80s did, which was to say, ‘Sit here and finish your food, and you can’t leave the table until you do.’” It would be a disaster with her son, she said. Studies show that parents’ forcing children to eat at mealtime can make them want to eat even less, and, for her son, “it would turn into a panic attack,” the mother said. “He would cry, he would vomit. It wouldn’t be about food anymore. It would be about torturing someone who isn’t trying to perpetrate a power struggle. He’s just refusing the food because he’s terrified of it.”

When a child won’t eat, it’s a natural reflex to find something — anything — that might give them sustenance. Many parents dealing with ARFID learn to anticipate their child’s reactions before a meal, trying to solve for every outcome: What can I serve that my child won’t refuse? What if she eats nothing? Will it turn into a fight? Parents of children with a sensory aversion to food describe going to great lengths to remove, say, a brown spot from a French fry or to mix pancake batter in just the right ratio and pour it into the only acceptable shape, all to provide the consistency that might make their child want to eat.

But while applying pressure can be counterproductive, specialists say that accommodating a child’s preferences entirely can lead to more rigidity, too. When ARFID appears with anxiety, the cycle, Kertesz-Briest said, goes like this: “We experience the fear stimulus, we avoid it, we feel better. We face it again, we avoid it, we feel better. The more we avoid, the scarier something becomes. In the case of ARFID, even avoiding one bite of one food one time can be what knocks it off the safe-food list.” She continues, “For parents who have kids with anxiety disorders, sometimes unknowingly we collude with the anxiety or we collude with the ARFID. The parent thinks, I know my kid will eat this one food, so I’m giving only this food to them, or I don’t want my kid to feel scared or uncomfortable, so I remove the discomfort right away. It’s a hard cycle to break out of.”

Parents don’t cause ARFID, but in their hypervigilance, their pursuit to help or protect their children, they can sometimes entrench it. “This is a very anxious parenting generation,” Zakreski, the clinical psychologist, told me. “You could make the argument that we are too attuned to our kids, that we are not really willing to challenge them in ways previous generations were.” (He’s not immune to this either, he admits — sometimes, he makes pasta three different ways for the same meal to appease his two children.) The modern food landscape doesn’t help. Restaurants, no matter the cuisine, attract parents with kids’ menus: a reliable list of mac ’n’ cheese, pizza, hot dogs, and chicken fingers. At the grocery store, entire shelves are dedicated to packaged snacks created specifically for children. “If you were somebody who had a tough time with milk and you were growing up in the ’80s, you were on your own,” said Zakreski. “Now, it’s like, ‘Do you want the oat milk? The almond milk?’” For some children, he said, more options increases the risk of ARFID.

Meanwhile, doctors are increasingly aware of how other family dynamics — especially parents’ stress about their child not eating — can reinforce the disorder. During mealtimes, “the kids feel the parent’s anxiety, even if the parent is trying to contain it,” said Wendy Nash Moyal, a psychiatrist who specializes in autism, OCD, ADHD, anxiety, and learning disorders. “So the child with ARFID experiences whole-body tension — the feeling that their throat is going to close up more. The child’s anxiety and the parent’s anxiety, both things are going to exacerbate the ARFID symptoms.”

Sharp of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta has also observed how a parent’s trepidation around their child’s eating can “spill over” onto that child. Two years ago, he saw a young patient with a severe food allergy. The boy had long restricted his diet, but after getting a stomach bug, he stopped eating his safe foods altogether. “The dad said, ‘I think I created this,’” Sharp recalled. Long before the stomach bug, his son had gone into anaphylaxis, and the father, terrified, became extremely vigilant about the foods his son ate. Now, he worried his vigilance might have contributed to his son’s anxiety. “And I said, ‘It’s not your fault. You didn’t know what to do, and this is scary.’”

At the restaurant, Grace acknowledged that she and her husband “do accommodate. We bend more than I guess a regular parent would.” Still, her pediatric endocrinologist is more concerned with her son’s growth than with his nutrition; blood tests show the boy has started puberty and, already short for his age, has grown only an inch in the past year — half of the minimum expected. “She’s panicking,” Grace said. For the better part of seven years, she has been taking her son from specialist to specialist without much improvement. She suspects there are people who blame her, but she also knows that while her son may not be eating a healthy, balanced diet, he’s not in a hospital, not on a feeding tube, and not relying on shakes for sustenance. “So if it’s just me feeding him lots of junk food, I don’t care.”

In March 2023, Amelia was ready to be discharged from the eating-disorder clinic. She still wouldn’t swallow anything, including water, so nurses met with Mark and Laura and trained them in how to use the feeding-tube equipment. Amelia’s psychiatrist prescribed an antipsychotic medication that balances dopamine and serotonin in the brain, along with an anti-anxiety medication. Drugs are not always used with ARFID patients, but in some cases, they can address a separate issue, like severe anxiety, that may be adding to the patient’s restrictive eating. Laura is a former pharmacist who is “very anti-drug” — the idea of putting their already small and weak daughter on psychiatric medication with potential side effects was scary, but ultimately she and Mark decided it was necessary.

Amelia was 40 pounds when she walked into school for the first time in a month. She was allowed to keep a small trash can next to her desk to spit in, and Mark would come in at lunchtime to give her food, fluids, and medication. At home, she continued the treatments she had begun in the hospital. With Kertesz-Briest, who is her psychologist, Amelia underwent cognitive behavioral therapy, a common treatment for other eating disorders that is currently one of the most promising interventions for ARFID. In CBT, a patient identifies their fears around eating, is exposed to different foods and tested on their negative predictions, and learns coping skills for periods of distress. She also attended regular feeding-therapy sessions, which, depending on the patient, can focus on the mechanics of chewing and swallowing or the sensory experience of eating — the way different foods smell or feel. In one session, Amelia cut pictures of food from magazines and organized them from easiest to swallow to most difficult to swallow, then made them into a game board.

Laura and Mark participated in the family- and feeding-therapy sessions too. They learned to serve small portions so as not to overwhelm her, to tell her she was safe when she struggled to eat rather than to pressure her, and to allow some distractions, including an iPad, which can be a helpful diversion for ARFID patients even if it goes against today’s no-screens mantra. They learned to adjust their language around eating, like coming up with a code word for dinner to alleviate some of the negative associations.

Separately, Laura and Mark worked on their own reactivity to avoid the familiar spiral of Amelia refusing to eat, her parents getting frustrated, and everyone becoming upset. Laura had been devastated to learn that, several months earlier, Amelia hadn’t wanted to leave the hospital — she felt scared at home with all the yelling. Laura, for her part, had begun to feel as though she and Mark had lost their ability to communicate; she had been thinking about divorce. At Mark’s suggestion, they started couples counseling. For the first time, Laura took medication for her own anxiety.

Most families turn to some combination of CBT and feeding therapy to help a child with ARFID, but because the diagnosis is relatively new, researchers are still exploring ways to treat it. In a recent trial for ARFID patients ages 5 to 9, Nancy Zucker, a clinical psychologist and director of the Duke Center for Eating Disorders, focused on acknowledging and repairing the trauma experienced by both the child and the parent as a result of the child not eating in order to ease their anxiety around mealtimes. For one of the activities, she had them cook together but not with the aim of taking a bite. With each positive experience, the child was instructed to put a marble in a jar. “It’s like the kid’s giving the parent a sticker,” Zucker said.

Some weeks, Amelia showed improvement, taking the smallest sip of water. Then she would regress and refuse even that. In therapy, she was learning coping mechanisms, breathing exercises, and new vocabulary to articulate how she was feeling. But she wasn’t putting them into practice in a way that resulted in the ultimate goal of eating or drinking. Mark and Laura, increasingly desperate and exhausted, started to make plans to readmit Amelia into an inpatient facility, and in August, a spot opened up at a highly regarded eating-disorder clinic. By then, Amelia’s psychiatrist had recommended weaning her off her existing medications and putting her on an SSRI. After more weeks of no improvement, he gradually increased the dosage until it was double.

Before they broke the news to Amelia that she would be going back to the hospital instead of to school, they decided to go on a hike with friends. It was hot, and the adults carried water bottles as they made their way up the trail. Amelia’s hydration still came from her feeding tube, taped to the small patch of skin below her nose. As they walked, Mark heard a small voice: “Dad, I’m thirsty.”

He looked around, checking that it hadn’t been one of their friends’ children. It was Amelia. “Oh, do you want some water?” he responded, trying to sound nonchalant. He handed her the bottle and watched in disbelief as she took one sip, then another, then another. The next day, they went to a noodle shop. Laura gave her a half-bowl. As Amelia slurped down her food, Mark and Laura squeezed each other’s hands beneath the table.

Doctors warned them not to get too excited. ARFID can follow young people into adulthood, and regressions are common. Something as simple as a change in packaging can cause a child with ARFID to suddenly distrust a food they’ve been eating. Parents worry about their kid catching a stomach bug or having strep throat, which may set them back. But it was hard for Mark and Laura not to give in to optimism. They called the hospital and canceled Amelia’s upcoming stay and contacted the school to let them know she would be starting third grade. One week later, after Amelia kept asking when she could remove the feeding tube, Mark took it out. When they looked at her reflection in the bathroom mirror, they both cried.

In his view, the SSRI calmed Amelia’s anxiety to the point where she was finally able to use the skills she had been learning for months in therapy. Nearly two years later, she’s still taking the medication, but her doctor has lowered the dosage. Mark is determined to get her off it altogether; one side effect of the higher SSRI dose was that Amelia started wetting her bed.

Amelia eats more now — pasta, fruits, and even beef, pork, and fish — but she still has anxiety. They have stopped the feeding therapy, wanting to let her go back to just being a kid. The family is still uncovering the full extent of what they’ve been through; last year, Amelia stiffened when the Kylie Minogue track “Padam Padam” came on — it was one of the songs on the radio during her months in treatment. The word choking is banned from their household. Amelia is happy at a new camp this summer. She loves anime and playing Roblox and dancing to K-pop. But Mark hasn’t shaken the fear that this isn’t the end. “Even talking about this now,” he said hesitantly, “I don’t want to jinx it.”

Source link

Several healthy eating patterns may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes across diverse ethnic groups

Eating Eggs Weekly Linked to Lower Alzheimer’s Risk, Study Shows

9 reasons why eating too much fruit may not be as healthy as you think